CBDCs: Pioneering the Future of Banking

Summary

Explore the future of secure, efficient digital transactions as MAS launches its 2024 CBDC pilot. Discover how this initiative aims to enhance banking, foster financial inclusion, and transform business operations, setting Singapore at the forefront of digital finance while navigating potential challenges in the traditional banking landscape.

Imagine a future where secure, swift, and efficient digital transactions are the norm. The Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS) is making this a reality with its 2024 Central Bank Digital Currency (CBDC) pilot, which entails the settlement of retail payments between commercial banks using “live” wholesale CBDC. Ravi Menon, Managing Director of MAS, emphasized the initiative’s significance at the Singapore FinTech Festival 2023, highlighting ‘MAS’s commitment to pushing the boundaries of financial innovation‘. This pioneering step, primarily focusing on enhancing domestic banking, could lay the groundwork for future transformations in how we manage both local and international finances.

What is CBDC?

A Central Bank Digital Currency (CBDC) is the digital equivalent of a country’s currency, backed and regulated by the central bank, ensuring secure and efficient transactions. CBDCs are of three types:

- Retail CBDCs: For the public, facilitating daily transactions.

- Wholesale CBDCs: For financial institutions, handling large transactions.

- Hybrid CBDCs: Merging both types, ideal for digital wallet-centric economies like Singapore.

Singapore’s blend of digital wallet usage and tech-savvy population makes hybrid CBDC more suitable. This model promises to mesh with existing digital payments effortlessly, bolstering transaction speed and broadening financial access for all, from everyday users to big institutions.

Impact on Individuals

The transition to a CBDC-dominated system marks a significant shift for Singaporeans, promising more stable and secure financial experiences, backed by the central bank’s regulatory framework.

CBDCs aim to bridge the financial inclusion gap by facilitating transactions without traditional bank accounts, particularly benefiting the underbanked and fostering greater economic participation and trust in the banking system. For instance, the introduction of eNaira in 2021 aimed to enhance financial inclusion in a country where a significant portion of the population lacks basic financial services, potentially enabling up to 90% of the Nigerian population to use eNaira. However, with 98% of the adult population in Singapore already account holders, the direct impact on financial inclusion might be less significant.

CBDCs could also introduce competition in payment systems, potentially lowering costs and encouraging innovation. Professor Rajan from the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy notes that CBDCs are anticipated to enhance the effectiveness of payment systems, given that the costs associated with processing cash payments can be notably substantial. Additionally, it serves as a robust framework for payment service providers to settle transactions efficiently. In scenarios where digital payments face challenges, such as cyberattacks or power outages, CBDCs is an alternative backup system, maintaining transaction continuity with heightened cybersecurity measures.

Revolutionising Business Operations

CBDCs can lead to a transformative shift in business operations, especially benefiting SMEs by enhancing transactional efficiency. For instance, SMEs could grapple with cash flow challenges due to delayed payments and high transaction costs. With CBDCs, these issues could be significantly mitigated, as transactions would be faster and more cost-effective. Thus, SMEs can reallocate resources more effectively, streamline their operations, and respond more rapidly to market demands.

Furthermore, businesses can leverage this technology to develop services and products that cater to a broader demographic, including those underserved by traditional banks. This approach not only taps into a new customer base but also promotes economic inclusivity. For example, companies could create platforms that facilitate microloans or savings programs for individuals who lack access to conventional banking services. By doing so, they not only fill a vital market gap but also contribute to the overall economic empowerment of underbanked communities.

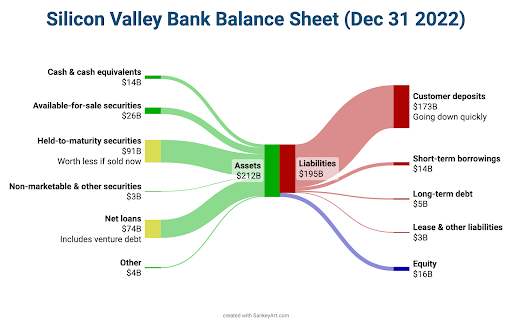

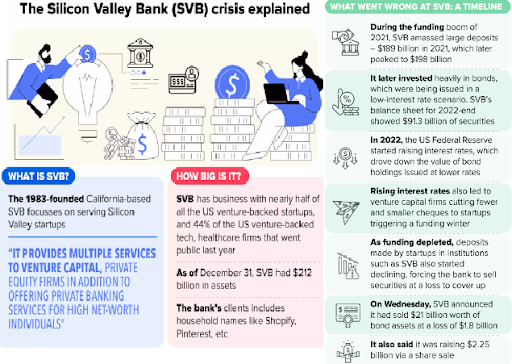

However, CBDCs also pose challenges to traditional banking, potentially reducing deposits as individuals and businesses might prefer holding CBDCs directly with the central bank.This shift could drastically reduce banks’ capacity to lend, possibly even precipitating bank runs if confidence in traditional banks decreases. While CBDCs’ security and central bank backing may boost user trust and mitigate bank run risks, reduced bank deposits could significantly reduce lending, affecting SMEs reliant on smaller banks for credit. These institutions might face a disproportionately higher impact than larger banks due to their more limited access to alternative funding sources.

As Singapore approaches the CBDC pilot, it’s crucial to stay informed, adaptable, and ready to embrace the associated risks while optimizing the benefits. Though challenges like potential impacts on traditional banking systems and security concerns exist, they can be managed through careful planning, regulation, and technological innovation. This initiative promises a more inclusive, efficient banking system and a transformative shift for businesses. By proactively addressing challenges and leveraging the opportunities that CBDCs present, we can confidently move forward, ensuring a resilient financial landscape that thrives in this digital era.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the National University of Singapore (NUS) or the NUS FinTech Lab.