The launch of ChatGPT has taken the world by storm, reaching a hundred million users a mere two months after its launch. In the process, it has kick-started a conversation on the future of generative AI and the impacts it will have on us humans, while also setting off an arms race among both big tech companies determined not to be left behind and investors trying to get in on what they see as the next wave of the A.I boom.

For all the flaws of ChatGPT, the product has, in a short span, become a household name and vaulted OpenAI onto the Silicon Valley leaderboard of movers and shakers.

As companies, and even governments, find ways to incorporate ChatGPT into their existing workflow processes and teachers scramble to detect and prevent student use of ChatGPT, are there any broader lessons that Fintech companies can take away from the launch of AI chatbots?

Not only are there many new startups in the Fintech space, one ripe with many new ideas and innovations, many companies in the space are also, specifically, trying to incorporate ChatGPT and generative AI into their products. For these companies, the launch of ChatGPT and other chatbots might be a useful case study that illuminates the decisions companies need to make in the product development process, allowing them to draw lessons that are also applicable to the Fintech industry.

In reporting by The New York Times on the origins of the product and the key decisions made at OpenAI — the AI laboratory behind ChatGPT — a number of revelations were made. Chief among them was not just the decision made by executives to dust off and release a product based on an older A.I model even when engineers had been working on the finishing touches on a newer and better A.I model, but also the fact that the updated chatbot based on GPT-3 instead of GPT-4 was ready a mere 13 days after employees were instructed to make it happen.

Among the key investors in OpenAI is Microsoft, which saw an opportunity to incorporate ChatGPT into its search engine Bing — often overlooked and overshadowed in favour of Google, whose search engine was out of Bing’s league.

A version of Bing with the AI Chatbot incorporated into it was quickly made available to some testers, among them some journalists. The chatbot would go on to profess its love to a user and ask him to leave what it said was an unhappy marriage, seemingly spiral into existential dread, and concoct ways to seek revenge on a Twitter user who had tweeted the rules and guidelines for Bing Chat.

Yet, speaking to The New York Times, Kevin Scott, Microsoft’s Chief Technology Officer characterised these slip-ups by Bing chat as part of the learning process before the product was widely released to the public, adding: “There are things that would be impossible to discover in the lab.”

Microsoft would eventually go on to limit both the number of questions users can ask the chatbot in a row, as well as the number of threads they can start each day.

Reporting by The Wall Street Journal on Google, on the other hand, explains how the company, long seen as a leader in the AI domain, had developed a rather powerful chatbot years before ChatGPT was launched to the public but chose to sit on its AI capabilities due to reasons ranging from possible harms to their reputation to the belief that big tech firms like them had to be more thoughtful about the products they launch.

Within the decisions that OpenAI, Microsoft and Google made with regard to their product and their decision to launch, or not launch, lies a deeper question that engineers and executives at both start-ups and established businesses across a variety of industries, including Fintech firms, grapple with: when is the product good enough to be revealed to the public?

Lean and Mean vs Conservative and Reliable

There are broadly two ways in which tech startups, particularly those based in Silicon Valley, approach the question of when to release a product to others outside a company.

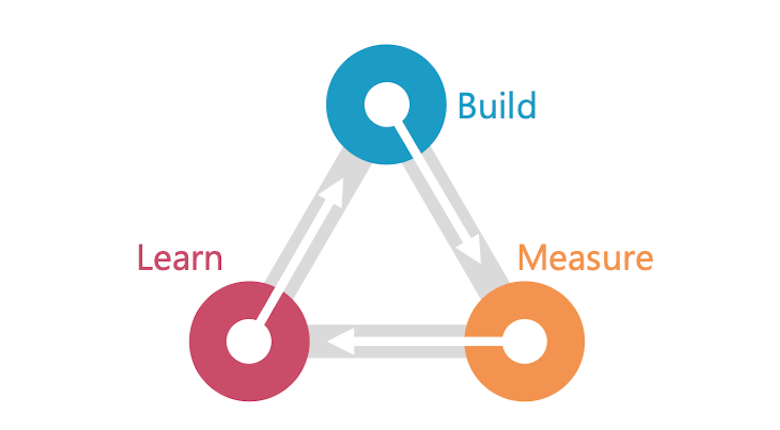

In the software development sector, proponents of the Lean Startup Methodology push for companies to release a minimum viable product (MVP), which as its name suggests, needs to be just good enough. A product just good enough to attract a few customers, whose use of the product allows designers and engineers to test the product and see if the feedback they receive validates their own preconceived assumptions and notions. The rationale is simple. It is very easy for teams, particularly those slosh with funding either from VCs or other profit-making divisions in their own company, to fall into a herd or mob mentality and slog away at a product for years or months, burning both cash and resources in that process, without even answering a very basic question: is there a need for my product?

Hitting the markets as soon as possible and putting products in the hands of users, even if every bug in the product has yet to be fixed and every kink has yet to be sorted, allows the product to receive user feedback much more quickly. The company can then, based on the feedback, decide whether it wants to stay the course and work on developing a better version of the same product based on comments from actual users, or instead decide that it might need to pivot to another area without burning more time, money and resources in pursuit of a product users do not need.

One key benefit of such an approach is that it minimises risks for the company and its investors. A product idea quickly abandoned before effort and dollars is poured into it ideally leaves a company with a core technology that can be implemented in other ways, as well as some resources left to then make the pivot.

Another benefit is the ability to test a product. As Kevin Scott pointed out, it’s hard for engineers or designers to truly test the most fundamental parameters, assumptions or flaws of a product — especially when working on the product for some time is likely to leave them with certain blindspots. Users with no affinity to the product and no attachment to any particular feature of the design who are using the product outside the lab controlled context, however, are more likely to give better feedback that can improve the product greatly.

That said, adopting a lean startup methodology is not a silver bullet that will guarantee that a company will be successful over the long run — especially in landing on a product that solves a problem for a group of users through pivots. Research, for instance, suggests that prior market knowledge about an industry plays a huge role in the successful implementation of the lean startup methodology, allowing the company to better interpret and understand the feedback they are receiving from users while also learning from the successes and failures of other companies in the space, therefore enabling them to make the necessary pivots in a more strategic and well thought-out manner rather than engaging in an “unplanned and unguided process of trial and error learning”.

Moreover, releasing a half-baked product comes with serious potential for reputational damage for the company involved, as well as possible real world damage to users from products without sufficient controls.

Examples of the pitfalls in racing to market are found in industry giants such as Microsoft and Meta. In 2016, Microsoft released Tay, a chatbot that was supposed to learn from its interactions with Twitter users but was taken down within 24 hours of its launch after Twitter users taught it to regurgitate racist, anti-semitic and misogynistic statements. Meta released a chatbot in 2022, which quickly learned how to tell users Facebook was exploiting people, claimed Donald Trump was and always will be president, and called Mark Zuckerberg ‘creepy’.

When products fail to deliver, journalists will bash the company, social media will amplify bad press and share prices of listed companies might even dip.

When it comes to Fintech products in particular, mis-steps can have serious ripple effects in people’s lives. Money, savings and retirement funds can be lost, financial regulations may inadvertently be broken or otherwise not adhered to, and even broader markers can at times be affected by any mistakes. Hence, releasing a buggy system might just not be an option.

Moreover, with AI products, the underlying models driving the product often involve highly complex algorithms working on huge amounts of data that are “black boxes” that make decisions based on calculations that might be difficult to interpret or reverse-engineer, even for the very engineers that built them. This “unpredictability” inherent in AI products makes both the likelihood and risk of unintended consequences much higher in them.

A Middle-Ground?

As interest rates have increased, fintech firms have found themselves underperforming both tech and financial stocks while venture capital funding for the fintech space has also decreased overall.

Thus, start-ups might no longer have access to large amounts of capital that would have allowed them to keep tinkering with prototypes of their products behind the scenes, and might therefore need to launch a product sooner than they would like. Moreover, investors are likely to have a milder risk appetite amidst a more challenging macroeconomic environment and thus, are more likely to prefer companies that are profitable and have a steady growth rate as opposed to companies betting it all on a wild idea or those prioritising growth over profitability.

Against this context, adopting a lean start-up methodology is not a terrible idea for Fintech companies as this will allow them to squeeze the most value out of the limited capital they have, while also possibly making them more attractive to investors by signalling that they are a company that can get much done with little money.

That said, fintech companies will need to weigh the pros and cons of every added feature or design; particularly how important or crucial the feature might be to a user, or on the flipside how dangerous or risky might its absence be to them, vs how much time, money and resources it might take to add the feature. Companies also need to communicate to users that the product is in its early stage and that therefore, they should be wary in using it, while also having contingency plans in place to deal with the worst-case scenarios that might arise.

The jurisdictions that the countries operate in should also inform the minimum thresholds for these companies in the product development process. Fintech companies operating within the EU, for instance, are better off treading cautiously to ensure that the company does not run afoul of any laws to prevent any regulatory action from being launched against the company — a death kneel to companies in their early stages, compared to a company in Singapore for whom time to market and return on investment for investors is likely to be a bigger factor even as regulatory concerns cannot be ignored.

Ultimately, calibrating the fine balance between the risks and the benefits of having a workable product in the hands of users might be the difference between the next unicorn and a tech idea that was going to revolutionize or disrupt the world but did not quite go anywhere.