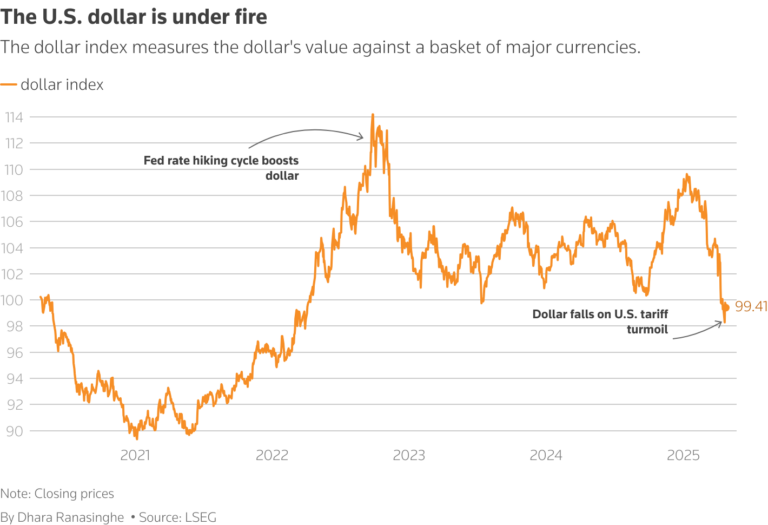

On April 2—“Liberation Day”—the Trump administration announced a series of tariffs aimed at boosting U.S. economic competitiveness. The move, however, simultaneously weakened the U.S. dollar, pushing it to a multi-year low. Nonetheless, the administration supported the decline as a necessary step to enhance the competitiveness of American exports and reduce trade deficits.

For over six decades, the Dollar has served as the world’s primary reserve currency and a safe haven for global investors, playing a central role in international foreign exchange reserves – 59% of all reserve currencies globally are in U.S. Dollars. But with these shifts, are we starting to witness the end for dollar supremacy? If so, what might this mean for the U.S. and global economy, and for the dynamics of the international monetary system?

Economics behind the Dollar’s depreciation

The Dollar depreciated by over 4.5% in April alone, marking one of its largest declines since 2009. Amid growing concerns that large-scale tariffs could slow U.S. economic growth and reduce expected returns on investment, investors’ confidence in the dollar waned, triggering them to sell off dollars in favor of alternative investments with higher returns.

But this is just one piece of the larger puzzle. In the first four months of 2025, the U.S. dollar has already slumped 8% against a basket of major currencies. This is a reflection of investor risk averseness from an uncertain climate in the U.S. upon the presidency of Donald Trump – not just tariffs, but also unpredictability in policies revolving around interest rates, Federal spending, and geopolitics. It directs capital outflow to currencies of economies with more optimistic growth outlook (for instance, Europe, after a sluggish year).

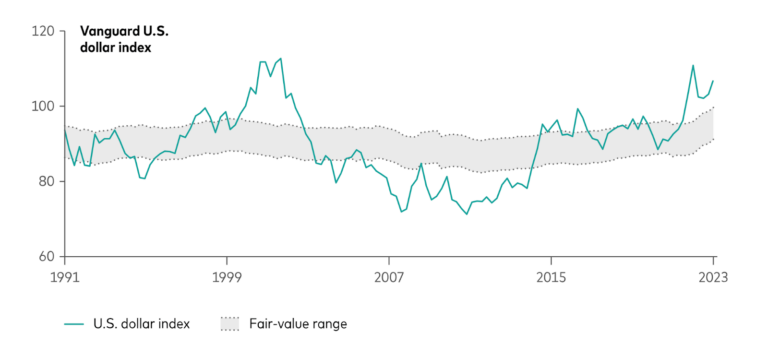

The phenomenon can also be interpreted as a natural market correction from a state of overvaluation. According to a proprietary model by Vanguard, the U.S. Dollar was estimated to be 12% overvalued relative to a basket of five other major currencies in late 2023. The model also indicated a 75% likelihood of the Dollar depreciating over the next decade. Over the past ten years, the Dollar has benefited from strong U.S. economic fundamentals, significant gains in per capita production driven by rising productivity, growing demand backed by expanding global trade, and overall bullish market sentiment. However, with rising recession risks and concerns on the White House’s ability to pay its national debt, the Dollar is expected to gradually realign with its intrinsic worth range evaluated on fundamental economic factors (i.e. fundamental value range) over the long term.

Implications on the U.S. economy and capital flow

A weaker Dollar makes U.S. exports more competitive and imports more expensive due to its reduced purchasing power. While this may support the White House’s aim of narrowing the trade deficit, it also risks importing inflation – especially given the stickiness of U.S. reliance on foreign goods, which cannot be easily or quickly substituted.

This effect extends beyond household goods and services. Commodities such as oil, gold, and industrial metals are priced in Dollars globally. When the Dollar weakens, commodities prices tend to go up as global demand increases – since they appear cheaper to foreign buyers in their own currencies. For instance, crude oil has a historic negative correlation with the U.S.D Index.

A weaker Dollar has not only allowed traditional safe-haven currencies such as the Japanese Yen, Euro, and Swiss Franc to appreciate, but has also made it an attractive funding currency for carry trades. It prompted substantial capital flows from low-yielding Dollar-denominated assets into higher-yielding emerging market currencies like the Brazilian Real, Indonesian Rupiah, Indian Rupee, and Turkish Lira, as well as their local bond markets.

Will the Dollar continue to be a reserve currency?

A reserve currency is one in which the majority of global trade and international transactions are conducted. The U.S. Dollar gained this status in 1944 following the Bretton Woods Agreement, largely due to America’s dominant role in World War II and its economic strength at the time. However, the Dollar ceased to be backed by gold in 1971, when President Nixon officially ended the Gold Standard.

Today, the Dollar faces growing skepticism as the world’s default payment currency. The current economic and geopolitical landscape has made it less attractive than in previous decades. Notably, during the sweeping sanctions imposed on Russia in 2022, many countries began to question the security of holding Dollar reserves—concerned that their assets could be frozen in the event of political disputes. This led to renewed interest in “de-dollarization” efforts, particularly among countries aiming to reduce dependence on the U.S.-centric financial system.

Several alternatives have been proposed as potential successors to the Dollar, but none are viable in the near term:

- The Chinese Yuan and Russian Ruble are tightly controlled by state authorities, limiting global trust and market openness.

- Cryptocurrencies face significant hurdles, including price volatility, regulatory uncertainty, and high energy consumption.

- Gold and other precious metals, while reliable stores of value, are impractical as reserve currencies due to transport, storage, and liquidity constraints.

Even if viable alternatives existed, replacing an entrenched reserve currency is a long and complex process. As Philip Alberstat, Managing Director at DBD Investment Bank, aptly notes: displacing the Dollar would require sustained global coordination over many years, as the institutional infrastructure supporting it – clearing systems, trading networks, and financial relationships – has taken generations to build.

While cracks in the system have begun to show, the structural dominance of the Dollar suggests it will continue to serve as the global reserve currency in the foreseeable future.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the National University of Singapore (NUS) or the NUS FinTech Lab.