Summary

Singapore, renowned for its business-friendly environment, faces an enigma: its IPO market trails behind global and regional rivals despite its status as a premier business hub. This article delves into the reasons for leading local startups like Grab and Sea Limited to choose foreign exchanges over the SGX, contrasts SGX with other Southeast Asian stock markets, and evaluates solutions to reinvigorate Singapore’s IPO landscape.

Ever since Singtel’s listing in 1993, the Singapore Exchange (SGX) had enjoyed the best market vibrancy and the highest trading volumes in Southeast Asia for 2 decades. Things went downhill after the infamous Penny Stock Crash in 2013 whereby the three penny stocks Blumont, Asiasons and LionGold suffered a colonial capitalisation loss in just a few days. Liquidity dried up, and the SGX became an “incredibly shrinking” market, as described by Bloomberg.

Despite Singapore’s stable political environment and favourable business atmosphere, SGX hasn’t attracted as many companies for listing as might be expected. In 2024 thus far, only one company has been listed on SGX: Singapore Institute of Advanced Medicine Holdings, a cancer-treatment provider. In 2023, SGX only saw six IPO deals, a decline from 11 deals in 2019. Surprisingly, even prominent domestic tech unicorns like Sea Limited, Grab and Razer have chosen to list on NYSE, NASDAQ and HKEX instead of SGX.

Here comes the million dollar question for Singapore: Is it attractive enough to attract tech companies for listing, compared to its Southeast Asian neighbours? How can Singapore create a more dynamic and hospitable market for these innovators?

What is an IPO?

IPO, or an Initial Public Offering (IPO), is a process whereby a privately-owned company sells shares of its stock for the first time to the public by listing them on a stock exchange. Through an IPO, the company can tap into a larger pool of capital to fund ambitious growth and expansion plans.

Is SGX still attractive for tech firms?

Many of these companies opted to list on exchanges outside Singapore to gain greater exposure to critical target markets as part of their expansion strategies, tap into a more extensive and varied investor base, or enhance liquidity and status.

US capital markets, in particular, are known to be more sophisticated and liquid with higher transaction volumes, therefore more supportive of tech start-ups’ listings than the low liquidity and low valuation stock market in Singapore. Additionally, SGX investors tend to be more risk averse, due to the typical Singaporean culture of seeking stability and the lack of proper investment education. Coupled with the fact that tech investments are inherently riskier, tech firms may find a narrower investor base in Singapore compared to other nations.

The diversity of industries among the companies listed on SGX is quite limited too, primarily consisting of asset-heavy companies. Notably, there is only 1 small video game art studio, Winking Studio, listed. The absence of listed companies in the Internet, software and communications sector may render SGX less attractive to tech and AI companies, given “companies prefer to list on a market with investors that know the firms and industry well to better support their growth strategies.” (Tay Hwee Ling, disruptive events advisory leader for Deloitte South-east Asia and Singapore)

An IPO at a historically well-established exchange is also often perceived as an accomplishment and success milestone. For instance, regarding Grab’s listing on the NYSE, chief executive of Vertex Holdings (Grab’s first institutional investor) Mr Chua Kee Lock noted that the move sends an important signal to investors and confirms Southeast Asia’s potential as a viable and attractive market capable of supporting global-scale winners.

IPO Scene in Southeast Asia

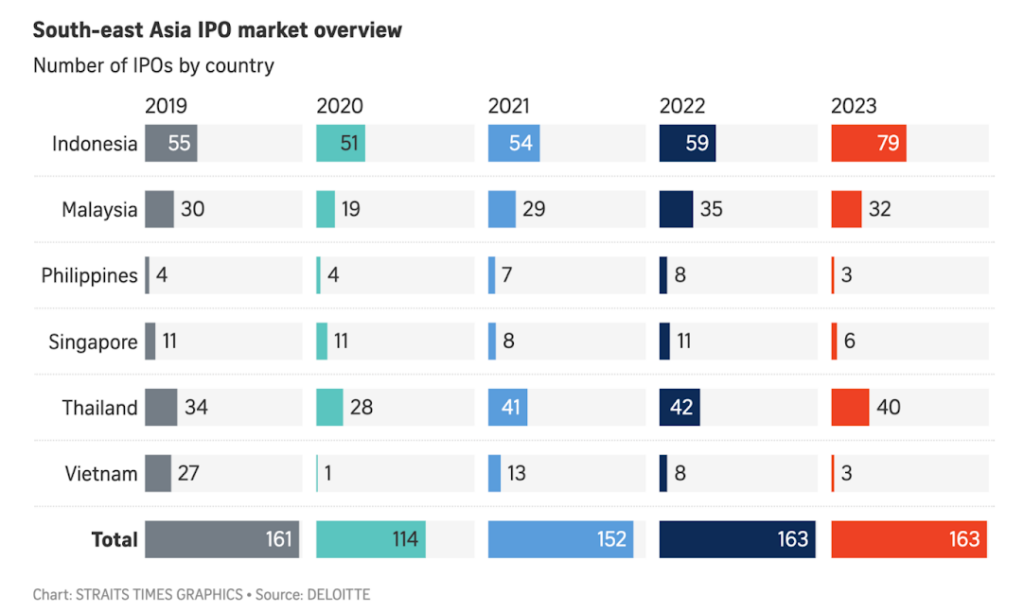

A 2024 Deloitte report suggests that nearby countries like Indonesia, Malaysia and Thailand experienced a more robust IPO landscape compared to Singapore. This phenomenon is particularly interesting, as it once again challenges the intuitive correlation between IPO deal volume and conduciveness of the business and political environment.

It is worth noting that these countries are developing countries currently experiencing transformative stages of economic growth and development. Coupled with the fact that they are also larger than Singapore, both in terms of population and land area, it is natural for larger scale business activities to take place over there. With a staggering majority of listed companies in Southeast Asia being local, these factors offer an explanation to the recent high listing figures in neighbouring bourses.

Also, the majority of the investors for the Southeast Asian stock market are locals. For developing countries, there has been a consistent increase in financial literacy as well as prominent technological advancements that make investments more accessible, thereby contributing to an expanding local investor base. In contrast, these metrics have remained relatively stable for Singapore.

The energy and consumer industries are highlights of the region’s listing activities. For example, the IPOs in Indonesia were led by listings from the renewable energy and metals and minerals sector, with five out of ten largest IPO deals in 2023 from this area. With growth in its energy and resources industry and the government’s determination to position Indonesia as a global hub in the electric vehicles supply chain, we can anticipate more green energy technology related IPO deals to come soon. Thailand and Malaysia similarly have strong IPO deals in the consumer sector, thanks to their growing affluent middle class.

How can SGX do better?

Efforts have been made so far to improve SGX’s appeal. This includes investments by Government-backed Anchor Fund @ 65 and Growth IPO Fund in multiple companies since 2022 and their close collaboration with portfolio firms to prepare these partner companies for IPO. It complements the Monetary Authority of Singapore’s (MAS) Grant for Equity Market Singapore (GEMS) scheme, which aims to help defray listing costs and increase research coverage of SGX-listed stocks. To broaden market access, there has also been ongoing collaboration with Thailand’s stock exchange on depository receipt listings.

Moving forward, additional incentives can be considered. For instance, Mr Masu Menon, OCBC Bank’s managing director of investment strategy, proposed allowing sovereign money and pension, like funds from the Central Provident Fund (CPF), to invest in the stock market. This move could boost investors’ confidence and enhance SGX’s liquidity. However, Mr Robson Lee, a partner for Kennedys Legal Solutions, cautioned that while the solution might provide a short-term boost, it might not be a sustainable solution for revitalising the local stock market. He pointed out that the CPF primarily serves as a savings plan for crucial medical and retirement needs, and corporate failures could adversely affect numerous CPF investors.

Conclusion

The journey to reviving Singapore’s previous IPO glory back in the 1990s is definitely an arduous yet crucial task to be tackled together by the government, financial institutions, venture capitals and promising entrepreneurs. As Singapore embarks on this voyage, continuous dialogue, adaptive policies, and a shared vision will be essential in overcoming challenges and seizing new opportunities in the evolving financial ecosystem. Together, we can not only reclaim past successes but also propel Singapore to new heights on the global IPO stage!

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the National University of Singapore (NUS) or the NUS FinTech Lab.