Summary:

Even if you live under a rock, you have probably heard of the abbreviation SVB by now. The collapse of Silicon Valley Bank has been the talk of the town in recent days — with regulators, financial markets and consumers all watching with eyes wide open to see what ramifications it might have globally. In this article, we explain how the bank came to collapse and what unpack some of the impacts it might have on the Fintech industry in Asia in particular.

What does the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank mean for Fintech?

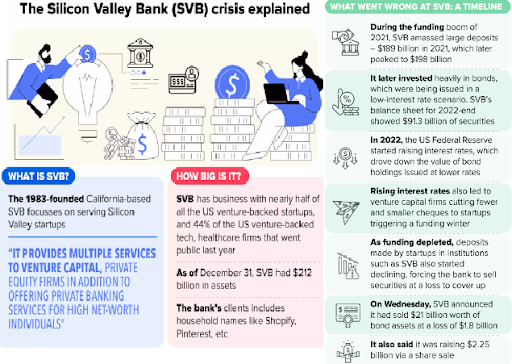

It started with a disclosure after markets had closed on Wednesday, March 8, that it had racked up $1.8 billion dollars in losses, after offloading US Treasury and government-backed bonds that were sensitive to interest rates and had thus depreciated in value.

Before Silicon Valley Bank could open on Friday, March 10, its assets had been seized by financial regulators, making it the largest bank to fail since Washington Mutual had collapsed at the height of the financial crisis in 2008.

As share prices of the bank tanked following the announcement that it had sustained great losses, venture capital backed start-ups — the bank’s main clientele — began pulling their deposits. The news of the deposit run spurred a further decrease in share prices, which prompted even more depositors to pull their money. The loss of confidence among shareholders and depositors fed into each other and sparked a bank run at a bank that was amongst the largest 20 banks in the US.

The bank, built over four decades, would come undone in a mere 36 hours — with its collapse reverberating through financial markets the world over. The stock price of other small and mid-sized banks in the US plunged in the aftermath of Silicon Valley Bank’s collapse, while shares in Credit Suisse over in Switzerland, already floundering, slumped even further and prompted the Swiss central bank to step in and announce that it would provide liquidity to Credit Suisse if necessary.

As the dust settles over the end of Silicon Valley Bank, what does its collapse mean for the Fintech industry?

A new era of Fintech

The collapse of Silicon Valley Bank was pretty much the outcome of a single trend — an increase in interest rates.

The way a traditional bank works is this: it takes in deposits from customers, paying them interest on their deposits to get them to keep their money at the bank.

It then takes the deposit and does a few things, chief among them lending the money to both individuals and organisations in the form of car loans, mortgages and credit lines. Banks can also invest some proportion of the deposits in instruments like treasury bills.

The spread it makes between the interest it pays depositors and the returns it earns on loans and other investments is the bank’s profit.

However, Silicon Valley Bank was not like the other banks.

Its business was focused on serving the needs of start-ups in Silicon Valley, which proved to be a lucrative gig while it lasted.

In an era of low-interest rates and a booming stock market through the 2010s, pension funds and hedge funds poured their money into Venture Capital funds in the hopes that the VCs would in turn invest their money in the next Amazon or the next Uber, giving them a huge payout and allowing them to beat the markets.

The VCs, slosh with cash, threw their money at tech startups that had lofty plans to change the world over the long term but little to show in the way of profits. Who needed a profitable business model or revenue streams when one could always raise another round from VCs?

VCs themselves were happy to provide more funding in subsequent rounds at a higher valuation, for an increase in a portfolio company’s valuation means returns on their investment, which allowed them to show investors that their money had grown and enabled them to raise even more money from them.

Startups, hence, prioritised growth at all costs — driven by the notion that if they grew more organically at a slower rate, their competitors or copy-cat firms would capture the market and that once they had grown large enough, economies of scale would kick in and give them a road to profitability.

The fiasco at companies like WeWork, for instance, was very much a product of this environment and mindset.

When VCs and start-ups were booming, Silicon Valley Bank was the banker of choice for founders and their venture capital backers. As startups raised more money from investors, they deposited them in the bank and allowed the amount of deposits in the bank to balloon.

Startups, however, did not need much in loans from the bank when they were getting funding from VCs. Besides, loaning money to businesses that earn no profits and often have little in collateral is a risky bet that most banks would hesitate to make. Hence, Silicon Valley Bank loaned out a lower percentage of the deposits it held than most banks.

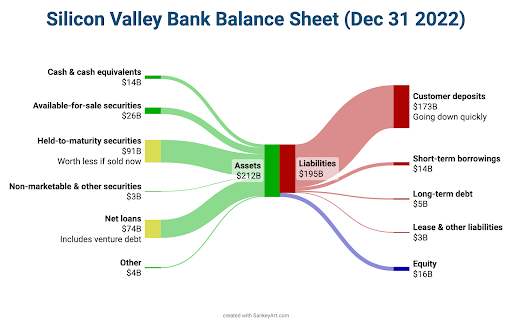

Yet, simply holding money does not pay out any money. Hence, Silicon Valley Bank invested a large amount of the deposits in long-dated securities like agency bonds and Treasury Bonds at a proportion much larger than other banks.

While it worked out well for the bank, the party came to an end when interest rates went up.

Investors became more conservative and less willing to put their money in VCs. VCs invested less money in start-ups and thus, start-ups deposited less money in Silicon Valley bank. As the inflow of deposits was slowing down, the long-term bonds that the bank had bet heavily on also depreciated in value and were worth less, with the double whammy of a slowdown in deposits and a decrease in asset values leading to the collapse of the bank.

As an analyst told Bloomberg, the collapse of Silicon Valley bank was the result of “Fed tightening extinguish(ing) froth from those parts of the economy with the most excess.”

With Jerome Powell having indicated that higher and faster interest rate hikes are necessary to temper inflation just prior to the Silicon Valley Bank saga, the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank may thus be a signal that this is the beginning of a new era for start-ups — one where higher rates make it harder to obtain funding.

While it remains to be seen if interest rates will be hiked again given recent events, if elevated interest rates persist, the days of start-ups burning through cash in an undisciplined manner to grow at all costs might be over.

Lofty valuations might become more grounded and founders might be pushed to be more fiscally responsible and more mercenary in the ways they deploy or use the capital they raise.

A correction to the years of excess in the start-up scene, however, is not inherently a bad thing.

Fintech’s dependence on traditional finance

Among the companies exposed to Silicon Valley Bank’s implosion was the major cryptocurrency player Circle Internet Financial.

The announcement that it had 3.3 Billion dollars tied up in the failed bank spooked investors, who cashed out around 2 Billion dollars worth of Circle’s USD stablecoin and led to the peg on the USDC stablecoin breaking.

After financial regulators announced that depositors in SVB will have access to all their money, the stablecoin, the second-largest after tether, came close to regaining its peg again.

DAI, the largest decentralised stablecoin, also lost its peg during the same period.

The woes that crypto companies faced was the result of turmoil not just at Silicon Valley Bank, but also the shuttering of Signature Bank by regulators after SVB went into FDIC receivership and Silvergate Bank announcing, even before depositors started pulling money from Silicon Valley Bank, that it was going to wind down voluntarily. All three banks had serviced clients in the crypto space.

As the columnist at crypto website Coindesk George Kaloudis writes, “Crypto has a banking problem, but banking doesn’t have a crypto problem”.

In other words, despite the occasional pundit who has tried to tie the banking crisis to the crypto winter only to be rebutted extensively, the collapse of cryptocurrencies and the companies in the crypto ecosystem has, by and large, only had a limited impact on banks and the broader financial system. The trouble at a few select banks, however, has had a disproportionate impact on cryptocurrencies.

Even as cryptocurrency firms have often pitted the crypto realm against traditional finance, selling the crypto world as a more transparent and equitable alternative to the world of traditional banking built upon fiat currencies, recent events reveal just how reliant much of the crypto industry is on the services and products offered by traditional financial institutions.

Far from building a separate world, they have built a world atop the financial infrastructure provided by the very institutions they wanted to make irrelevant.

With turmoil in banks across the world roiling the global financial markets, already weary banks are more likely to avoid servicing seemingly volatile Crypto companies, with some going even further to limit customer payments to Crypto exchanges.

Over the longer term, this also raises serious questions about the value proposition of cryptocurrencies.

Widespread disillusionment with the mainstream financial system was among the reasons why Bitcoin as a product, based on the idea of de-centralisation, took-off after the 2008 financial crisis, finding a following among many who saw crypto as an alternative realm in which bankers who got bailed out with taxpayer dollars did not keep paying themselves huge bonuses while the average joe got laid off.

The premise that centralisation and government intervention is a problem that needs to be fixed with cryptocurrencies, however, has been undermined by what happened with Silicon Valley Bank. The swift action by the authorities to make depositors whole is demonstration of the fact that perhaps, there is value in having a centralised financial system where a single authority, backed by the legitimacy vested in it by the powers of the state, can step in and calm things down or fix things when things go awry, something De-Fi protocols will not be able to do.

Impact on the asian market

While start-ups in Singapore have not been entirely immune from what happened across the world in Silicon Valley, on the whole, it has had a limited impact on both the start-up scene and the economy at large for now.

As a corporate lawyer who specialises in Southeast Asian tech told the financial daily The Business Times: “Southeast Asia is quite far removed from the action, but there are still a number of parties with banking relationships with SVB, so we’re not totally immune.”

The Business Times also reported that companies and investors in Southeast Asia were rushing to assure stakeholders they either had zero or limited exposure to SVB.

Amidst this, Singapore’s central bank put out a statement saying that Singaporean banks were well-capitalised, had healthy liquidity positions and had insignificant exposure to the failed banks in the United States, adding that any potential feedback on Singapore startups was also limited.

Analysts also noted that Asian banks held a low proportion of their assets in investments compared to SVB, and also maintained more-than-ample liquidity coverage ratios of 120-250%, making a scenario like that at SVB unlikely even as the effect of interest rate increases continues to kick in.

Even then, the stocks of Singaporean banks were hit by what happened, both in the US and with Credit Suisse.

Following what happened at Silicon Valley Bank, Vietnam became the first central bank in Asia to cut interest rates. While MAS’ managing director Ravi Menon had previously said that the tightening cycle had ways to go, it remains to be seen if SVB’s collapse will change the calculus.

The more persistent inflation is and the higher interest rates have to be increased to clamp down on inflation, the less likely a “soft-landing” becomes, increasing the likelihood of tipping into a technical recession. The more worrying possibility of a deep recession, however, is now emerging as a possibility as financial markets have been rattled by recent events and many fear that this is the start of a potential banking crisis that might threaten the global economy.

A recession will no doubt have great impacts not only on both workers and companies, but is also likely to further decrease the funding available to fintech startups while also potentially hurting their business prospects.

The run on the banks is also likely to lead to banks, particularly small and medium-sized ones facing heightened scrutiny, to increase lending standards — decreasing the availability of credit in the short to medium term. The tightening of lending, the grease to the economic machine, is likely to have an adverse effect on individuals, businesses and the economy as a whole, slowing down growth and also making a recession more likely. The fact that these smaller banks are more likely to serve smaller businesses and consumers bodes badly for those groups.

Is more regulation the answer?

A 2018 law passed in the US raised the threshold at which banks are considered systematically risky to 250 billion from 50 billion. Systematically risky banks are subject to stricter oversight from the government.

SVB had more than 200 billion in assets at the end of 2022, falling just under 250 billion and hence being spared more stringent stress tests and stricter scrutiny from regulators. The demise of the bank, of course, has brought into question the wisdom of the 2018 move.

In the age of social media and the internet, panic and contagion spreads much faster in the markets, making and breaking institutions within the blink of an eye. In this new world we inhabit, a lot more banks and financial institutions are, if not too big to fail, unlikely to go gently into the good night. Hence, in the interest of stability in not just the financial markets but in the economy as a whole, regulators should consider subjecting more banks and institutions to stricter scrutiny and more stringent regulatory requirements.

In conclusion, the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank has had a far-reaching impact on the fintech industry and the global economy. In the US, it has led to a lack of trust in the banking system and has sparked fears of a looming recession. At the same time, it has demonstrated the degree to which the fintech industry is reliant on traditional finance, and has caused some to reassess the value proposition of cryptocurrencies. In South-East Asia, start-ups and investors are being asked to provide assurances to stakeholders regarding their limited exposure to the failed bank. As we look to the future, it remains to be seen just how severe the long-term repercussions of the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank will be and how these will shape the future of the fintech industry.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the National University of Singapore (NUS) or the NUS FinTech Lab.